I get this question all the time: what is a cult, exactly? Over the years I’ve learned that the answer is complicated. Somewhere along the way, it seems like everything became a cult.

Swifties? A cult.

MAGAheads? A cult.

Musk Bros? A cult.

It seems cults are now simply passionate ideas gone wrong. Or at least, that’s how we talk about it now. The meaning of "cult", however, has shifted over time, bending to fit cultural anxieties and obsessions.

Before Charles Manson assembled his band of murderous hippies, "cult" wasn’t such a loaded term. It described small, fringe religious movements—offbeat, but not necessarily sinister. In fact, many groups that were once considered cults, like the early days of Mormonism or Seventh-day Adventism, eventually transitioned into mainstream religions.

Then came Manson

His Family became the boogeyman of the counterculture era—drugs, free love, radical ideas, and now, brutal murder. Suddenly, "cult" wasn’t just about religion; it was about control, violence, and brainwashing.

And the fear only escalated.

By the '70s, alternative religious movements were flourishing, and so were the fears about them. The Jesus Movement, Hare Krishnas, and other spiritual collectives were gaining popularity. Some were harmless, but others wielded deep control over their members. Then, in 1978…Jonestown.

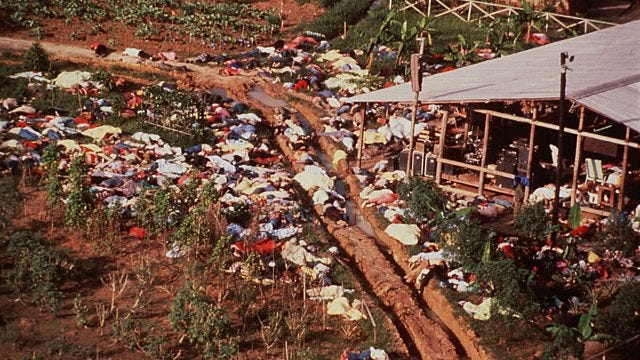

Over 900 people died in a mass murder-suicide in Guyana, and the country freaked out. Cults were no longer just fringe oddities—they were existential threats.

The images from Jonestown were horrifying: rows of bodies, cyanide-laced Flavor Aid, and chilling recordings of Jim Jones commanding his followers to die for their cause. Suddenly, "cult" became synonymous with totalitarian mind control. The idea that someone could be brainwashed to the point of self-destruction shook the public to its core.

A wave of anti-cult activism followed. Families claimed their loved ones had been "brainwashed," and groups like the Cult Awareness Network (CAN) emerged to fight back. Suddenly, any religious movement that deviated from the mainstream risked being labeled a cult. And once that happened, society saw you as dangerous.

Deprogramming became a huge (and controversial) practice during this time. Families, terrified that their children had been sucked into cults, hired deprogrammers—some of whom literally kidnapped and forcibly "reprogrammed" members to break them free. Whether these groups were actually harmful or not, the hysteria surrounding cults meant that nuance was often lost.

Fast forward to now. The rise of true crime storytelling has turned cults into binge-worthy entertainment. Wild Wild Country, The Vow, countless Jonestown and Waco deep dives—we eat this stuff up. And in doing so, we’ve made "cult" into a kind of aesthetic.

The word has lost some of its bite. It’s no longer just about control and coercion. Now, we use it to describe anything with an intense following.

Love a brand too much? Cult.

Obsess over a political leader? Cult.

Follow a fitness guru religiously? Cult.

The term is now used for SoulCycle, CrossFit, and even skincare brands. We joke about “cult-favorite” beauty products and "cult status" movies. It’s a shorthand for devotion, loyalty, and obsession.

I’m not trying to gloss over the mechanisms that make cults function—charismatic leaders, groupthink, an "us vs. them" mentality—they clearly exist everywhere. We see it in political movements, internet communities, and celebrity worship.

Take something like QAnon. It has all the trappings of a cult—deep faith in a charismatic figure, an apocalyptic worldview, and an unwillingness to accept contradictory information. The same could be said for certain influencer followings, where fans blindly defend their favorite personalities, even in the face of clear wrongdoing.

So where’s the line? When does passionate fandom become something more sinister? And should we be more careful about how we use the term "cult"? Who benefits from the way we use it?

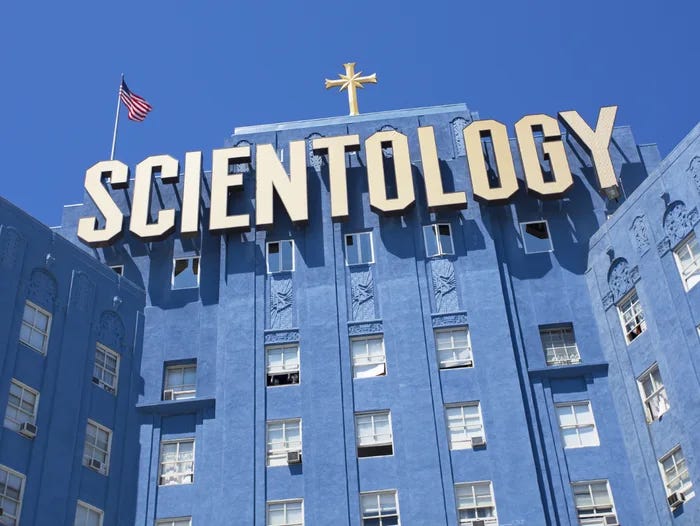

There are still real, high-control groups that isolate members, demand total obedience, and manipulate their followers. When we call everything a cult, we dilute the urgency of those stories. We blur the line between real harm and passionate fandom.

At the same time, maybe the word has stuck around because we recognize something cult-like about modern life. Social media echo chambers, parasocial relationships, intense brand loyalty—it’s not Jonestown, but the mechanisms of control and devotion are familiar.

What do you think? Where do we go from here? Do we keep using "cult" as a catch-all? Or do we start being more precise about what actually constitutes one?

Share this post